Matthew Derrick is a PhD candidate in Geography at the University of Oregon (USA). Focused mainly on the Russian Federation, and especially its non-Russian regions, his scholarly interests include ethno-territoriality, nationalism, regionalism, and geopolitics. He also nurtures an interest in cartography and geographic information systems (GIS). Most recently, his articles have appeared in the Journal of Central Asian and Caucasian Studies and Central Eurasian Studies Review. With the support of a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship, he is currently conducting fieldwork in Kazan, Russia, where he is investigating the relationship between Islam, nationalism, and territoriality.

Abstract

The policy of ukrupnenie (“merging”), which combines multiple federal subjects of the Russian Federation into unified, enlarged political-territorial units, is the latest phase in the Kremlin’s bid to restore central authority over its internal periphery. To date, this policy has reduced the number of Russia’s regions from 89 to 83, and more mergers are slated for the future. Vladimir Putin, along with the Russophone press, states that ukrupnenie is intended to reduce the severe interregional socio-economic inequalities in Russia by linking poorer regions to wealthier neighbors. This article refutes this stated rationale. In the process of analyzing mergers that have already taken place and those that are planned for the future, it is asserted that ukrupnenie in fact should be viewed as part of Moscow’s nationality policy, in turn a de facto continuation of Soviet nationality policy.

Keywords: Russia’s federalism, merging, ukrupnenie, political-territorial units, Moscow’s nationality policy

Introduction

The latest phase in Moscow’s campaign to restore central authority over its regions is the policy of ukrupnenie (“merging”), which amalgamates multiple federal subjects[1] into unified, enlarged political-territorial units. Since late 2005, a series of five mergers has reduced the number of federal subjects from 89 to 83, quite some distance from the ultimate goal of 40 or 50.[2] Russian President-cum-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin insists that the purpose of ukrupnenie is to “solve social-economic problems” in impoverished regions by linking them to wealthier neighbors, in the process slashing resource-draining regional bureaucracies.[3] The Muscovite press echoes this justification, asking who is “next in line for merging?”[4] and how “many subjects does the federation need?”[5] Glaringly absent from the discussion is a critical why?

The aim of this contribution is to redress this missing why with the assertion that any discussion concerning system-wide change to Russia’s political-territorial structure tout court should include a consideration of its nationality policy. It would be remiss to suggest that Russophone observers ignore the connection between ethnicity and center-region politics. Indeed, it is frequently claimed that the Kremlin’s current regional policies are crafted in response to the political-territorial chaos of the 1990s, a period when many of Russia’s ethnic republics operated virtually independently of the federal center.[6] Missing from these analyses however, is the recognition that the present grappling over federalism, and the role which nationality plays in shaping its future, is not merely a Putin-era answer to the Yeltsin-era “parade of sovereignties,” the devolution of power which, in the process of creating major regional wealth disparities, challenged the territorial integrity of the federation. Rather, as I contend, the merging of regions should be seen as a continuation of a much longer-standing nationality policy.

Setting the Stage

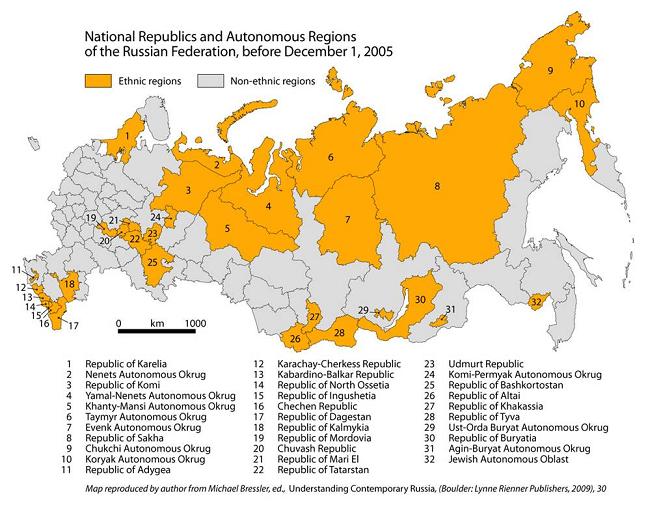

A cursory overview of Russia’s political-territorial structure is necessary. The Russian Federation is comprised of a hierarchy of units that can be separated into two basic categories: ethnically-defined republics and autonomous okrugs, and non-ethnic oblasts and krais (see the map in the appendix). The former are designated as the historic homelands of non-Russian titular populations, bestowing important national minorities with certain privileges.[7] The latter, inhabited almost exclusively by ethnic Russians, traditionally have enjoyed no special status. This ethnicity-infused federal structure is a Soviet legacy. The Bolsheviks granted the country’s most important national minorities autonomous republics, which, while distinguishing them from the fifteen union republics (i.e. the Baltic republics, Ukraine, Belarus, etc.), were created to give Russia’s minorities a veneer of statehood that papered over strict political, economic, and cultural centralization.[8] With the demise of the USSR, however, the more powerful ethnic republics and autonomous okrugs used their accoutrements of statehood to leverage varying degrees of de facto autonomy from a weakened center. In short, the federation Putin inherited was a system of extreme “economic, ethnic, and territorial asymmetries.”[9]

The policy of merging regions is only the most recent in a string of decisive moves made by Moscow since 2000 to reassert central primacy over its internal periphery. The first was the creation of seven federal districts, each headed by a Kremlin-appointed representative to oversee the harmonization of regional laws with federal constitutional norms. In the process, many functions previously carried out by regional institutions, such as tax collection, statistical data gathering, certain court procedures, etc., were taken over by federal agencies. In 2008, it was estimated that “the ratio of federal to regional powers over regional policy became roughly 70 percent to 30 percent,” a figure roughly inverse to what it was prior to Putin’s ascent to the Russian presidency.[10] Following the Beslan school hostage crisis in September 2004, a tragedy resulting in the deaths of more than 300 people, Putin canceled popular elections of regional governors and republic presidents, decreeing that thenceforth all regional heads must be approved by the Kremlin. Unable to appeal to their constituencies, governors suddenly became more amenable to the merging of their regions with neighboring subjects.[11]

It should be noted that, judging by the referendums which have preceded the political-territorial mergers, affected populations generally have responded favorably to ukrupnenie. In each of the completed referendums, significant majorities have approved of plans to join up with neighboring subjects. However, as in Russia-wide parliamentary and presidential elections, campaigns preceding the referendums on merging should not be considered fair and open. State-controlled media, along with other governmental resources, were mobilized to drive home the message that the merging of regions would lead to greater economic performance; countervailing opinions were excluded from the discussion. This vision of economic prosperity was repeated by regional governors who had gained the Kremlin’s favor, including Krasnoyarsk Governor Aleksandr Khloponin, who said the merging of his region with two neighboring autonomous oblasts would lead to a “new industrialization of Siberia.”[12]

Evaluating Putin-Era Regional Reforms

What can one make of Putin’s territorial-political reforms? If, as the Kremlin has repeated, the primary aim of the reforms indeed was to improve the economic performance of poorer regions vis-à-vis wealthier regions, they can be considered an unequivocal failure. According to the 2007 United Nations Human Development Report, regional inequalities in the Russian Federation have grown, not subsided, under Putin’s watch.[13] The Russian Ministry of Regional Development itself reports that the industrial output of the top ten regions outpaced that of the bottom ten by 33.5 times in 2006, a ratio that increased to 39.1 the following year.[14] The widening gap, according to several observers, is attributable to the functionary replacement of regional bureaucracies by federal cadres who, though empowered with significant central subsidies, are unresponsive to the actual needs of local citizenry.[15]

Such explanations of growing regional inequality are likely to be accurate. However, they are posited on the error of taking Moscow’s declared aim at face value. If the main goal in fact were to improve the socio-economic status of the country’s neediest areas, then one reasonably would expect the policy of ukrupnenie to be guided foremost by the principle of urgency, defined by population size (the larger, the more urgent) and relative poverty. Following these criteria, at the head of the line would be the oblasts of the central and northwest federal districts suffering from the effects of prolonged deindustrialization, the poverty-stricken Muslim republics of the North Caucasus, and the poorest ethnic enclaves of the Middle Volga Basin, such as Mari El and Mordovia.[16] However, to date none of these regions has been merged, and none is slated for merging in the immediate future.

Analyzing Completed Mergers

A brief examination of regional mergers already accomplished indicates that a rationale based on ethnicity, not primarily on socio-economic concerns, underpins the policy. In each case, one or two ethnically-defined autonomous okrugs were merged into one or two non-autonomous neighbors, resulting in a single, larger oblast or krai (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Referendum Date | Merger Date | Merging Subjects | New Merged Subject |

| December 7, 2003 | December 1, 2005 | Perm Oblast + Komi-Permyak Autonomous Oblast | Perm Krai |

| April 17, 2005 | January 1, 2007 | Krasnoyarsk Krai + Evenk Autonomous Oblast + Taymyr Autonomous Oblast | Krasnoyarsk Krai |

| October 23, 2005 | July 1, 2007 | Kamchatka Oblast + Koryak Autonomous Oblast | Kamchatka Krai |

| April 16, 2006 | January 1, 2008 | Irkutsk Oblast + Ust-Orda Autonomous Oblast | Irkutsk Oblast |

| March 11, 2007 | March 1, 2008 | Chita Oblast + Agin-Buryat Autonomous Oblast | Zabaykal Krai |

Source: Generated by the author

Erased from the resulting subjects is any indication that an area within them previously was considered a historic homeland of a non-Russian nationality. Whereas indigenous populations formed outright majorities in two of the previously autonomous regions (Komi-Permyak Autonomous Oblast and Agin-Buryat Autonomous Oblast), and more than a quarter of the population in another two (Koryak Autonomous Oblast and Ust-Orda Buryat Autonomous Oblast), they form small, nearly insignificant minorities in the resultant mergers (see Table 2).

Table 2

| Merged Krai/Oblast | Assimilated Nationality | Autonomous Population | Merged Population | Autonomous Percentage | Merged Percentage |

| Perm Krai | Komi-Permyaki | 80,327 | 183,832 | 59.0% | 6.2% |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | Nentsy | 3,054 | 6,254 | 7.6% | 0.2% |

| Kamchatka Krai | Koryaks | 6,710 | 14,038 | 26.7% | 3.7% |

| Irkutsk Oblast | Buryats | 53,649 | 134,214 | 39.6% | 4.9% |

| Zabaykal Krai | Buryats | 45,149 | 115,606 | 62.5% | 9.4% |

Source: Generated by the author

Stated rationale is further undermined when considering economic situations of the pre-amalgamated subjects. Taking comparative capital investment figures as an indicator, it is seen that only in two instances did formerly autonomous regions merge with (only marginally) wealthier oblasts or krais (see Table 3).

Table 3

| Merged Subject | Pre-MergedSubjects | 2005 Per Capita Capital Investment(Rank Among All Federal Subjects) |

| Perm Krai | Perm OblastKomi-Permyaki Autonomous Okrug | 3054 |

| Krasnoyark Krai | Krasnoyarsk KraiEvenk Autonomous OkrugTaymyr Autonomous Okrug | 3978 |

| Kamchatka Krai | Kamchatka OblastKoryak Autonomous Oblast | 5028 |

| Irkutsk Oblast | Irkutsk OblastUst-Orda Autonomous Oblast | 5887 |

| Zabaykal Krai | Chita OblastAgin-Buryat Autonomous Oblast | 4838 |

Source: Generated by the author

In the case of the formation of Krasnoyarsk Krai, resource-rich Evenk and Taymyr autonomous okrugs were subsumed by a significantly poorer – albeit geographically larger – subject, in the process forfeiting formal recognition of their cultural distinctiveness. Future mergers will immediately result in the disappearance of remaining autonomous okrugs,[17] but also discussed are eventual mergers to erase ethnic republics, first of all the impoverished republics of Buryatia, Altai, Adygea, and Ingushetia. It can be assumed that after the economically laggard ethnic republics have been erased, the policy of ukrupnenie will be targeted at the more prosperous among them.

Conclusion

Discussing the merging of ethnic autonomies, Boris Makarenko, a Kremlin-associated pundit, contends that this regional policy will “logically correct … historical accidents,”[18] i.e. the Soviet-era formation of minority homelands within the greater Russian expanse. The more fundamental accident, however, is viewing ukrupnenie as a correction to history when in fact it should be seen as a continuation of Soviet nationality policy. As cultural-political geographer Ronald Wixman effectively argued more than two decades ago, Soviet-era nationality policy had as its primary goal “the maintenance of the territorial integrity of the USSR and the political power of the Soviet state.”[19] Whenever that integrity was threatened, the Soviet regime would grant temporary freedoms to its minority groups, but as soon as that threat dissipated, those privileges were revoked.

This same basic principle guides post-Soviet nationality policy. Much as Lenin granted territorial autonomy withinthe USSR to certain non-Russian nationalities as a strategy to reconstruct the Tsarist Empire, so too Yeltsin ceded unprecedented freedoms to ethnic autonomies to keep them from exiting the Russian Federation. Once they had established firm control over the Soviet territory, Stalin and his successors rescinded prior freedoms as they carried out de facto Russification schemes. And it is from this historical vantage point that the policy of ukrupnenie should be viewed. As ethnic autonomies are merged into larger oblasts and krais, so too are minority ethnic groups merged into a vaster ethnic-Russian nation.

[1] The constituent political-territorial units of the Russian Federation are generically referred to in Russian as “subjects” (sub’ekty). This is in light of a hierarchy of classifications addressed in this article below.

[2] Julia Kusznir, “Russian Territorial Reform: A Centralist Project that Could End Up Fostering Decentralization?,” Russian Analytical Digest, June 17, 2008: 8-11.

[3] Vladimir Putin, “Ezhegodnaya bol’shaya press-konferentiya” [Annual Large Press Conference], Kremlin.ru, February 14, 2008, http://www.kremlin.ru/appears/2008/02/14/1327_type63380type82634_160108.shtml (accessed June 3, 2009).

[4] Vladimir Kuzmin, Pavel Dul’man, “Kto sleduiushii v ocheredi na ob’edinenie?” [Who is Next in Line for Merging?], Rossiiskaia Gazeta, March 26, 2004, http://www.rg.ru/2004/03/26/sliyanie.html (accessed June 3, 2009).

[5] Boris Rodoman, “Skol’ko sub’ektov nuzhno federatsii?” [How Many Subjects Does the Federation Need?], Polit.ru, July 19, 2004, www.polit.ru/lectures/2004/11/04/rodoman.html (accessed June 3, 2009).

[6] For example, see Izvestia, “Natsional’nye respubliki protiv ukrupneniya regionov” [National Republics against the Merging of Regions], April 20, 2005, (http://www.izvestia.ru/politic/article1637892/ (accessed June 3, 2009).

[7] For example, Russia’s ethnic republics are permitted to have their own presidents and state symbols, and, according to Yeltsin-era legislation, have the right to decide their own state languages. Typically, the ethnic republics declared their native language and Russian as the state languages.

[8] The hierarchy of constituent units that was created after the 1917 Revolution loosely mirrored the Marxist-Leninist conception of nationhood, which made a distinction between a “nation” (natsiia) and a “nationality” (natsional’nost’ or narodnost’). A nation was viewed by Bolshevik theoreticians as a more developed cultural entity than a nationality and as one that warranted a greater deal of self-government.

[9] Elizabeth Pascal, Defining Russian Federalism (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2003), 3.

[10] Darrell Slider, “Russian Federalism: Can It Be Rebuilt from the Ruins?” Russian Analytical Digest, June 17, 2008: 2.

[11] The Kremlin has cajoled previously obstinate heads of regions slated for ukrupnenie into cooperation by offering them promotions in federal government. For example, the former governor of Tyumen recently was appointed to Putin’s cabinet for helping to orchestrate the imminent merging of his oblast with neighboring autonomies.

[12] Quoted in Vladimir Radyuhin, “Russian Regions Merge to Speed Up Growth,” The Hindu, April 20, 2005, http://www.hindu.com/2005/04/20/stories/2005042000061500.htm (accessed July 12, 2009).

[13] United Nations Development Program, National Human Development Report, Russian Federation 2006/2007: Russia’s Regions: Goals, Challenges, Achievements, 2007, http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Russian%20Federation/Russian_Federation_NHDR-2006-2007-Eng.pdf (accessed June 3, 2009).

[14] Minregionov, Osnovnye Tendentsii Razvitiya Regionov Rossiiskoi Federatsii v 2006-2007 Godakh (Sbornik Materialov) (Moscow: Minregionov, 2008).

[15] See Kusznir, 2008; Elise Giuliano, “Succession from the Bottom Up: Democratization, Nationalism, and Local Accountability in the Russian Transition,” World Politics, vol. 58: 276-310.

[16] See UNDP, 2007; Rosstat, Regiony Rossii: Sotsial’no-Ekonomicheskie Pokazateli 2005 (Moscow: Rosstat), 2006.

[17] That autonomous okrugs are slated for disappearance first should come as no surprise. Most were created as historic homelands for small-numbered shamanist-animist peoples of the Siberian north. They first appeared on the map in the 1920s and ‘30s as “matryoshka” subjects, i.e. a small political-territorial units contained within larger oblasts or krais, apparently intended to recognize the areas as historic homelands of indigenous peoples without affording them the full administrative rights of ethnic republics. It was only in the 1990s that the autonomous okrugs, like the republics, took significant control of their territories.

[18] Quoted in Kuzmin, Dul’man, 2004.

[19] Ronald Wixman, “Applied Soviet Nationality Policy: A Suggested Rationale,” in Passe Turco-Tatar – Present Sovietique: Etudes Offertes a Alexandre Bennigsen, ed., Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay et al. (Lovain: Editions Peeters, 1986), 450.