Prof. Hans-Georg Heinrich is a professor of political science at the University of Vienna, Austria, and specializes in empirical methodology and post-Soviet studies. He has worked as mission member for international organizations including for the OSCE in Georgia.

Kirill Tanaev is a Moscow-based journalist (Program Director, “CIS News/Vesti.SNG”, Vesti TV), who specializes in post-Soviet political systems. He is the General Director of the Foundation for Effective Politics in Moscow.

Abstract

This paper reports on an ongoing media research project that examines the coverage of the Russian-Georgian war in August 2008, in selected Russian, Georgian, and Western print media. Using computer-assisted content analysis, it presents evidence that print outlets display distinct patterns of either balanced reporting or partisan attitudes, which also vary over time. The effects of possible “spin” in independent print media have remained marginal and ephemeral. At least as far as US media are concerned, this could be the result of soul-searching following the war on Iraq.

Keywords: Georgia, Russia, media coverage, South Ossetia, computer-assisted content analysis

Introduction: Background & Rationale

According to a well-known truism, the first victim of war is truth. Nevertheless, since there are different wars and different societies, truth follows a variety of trajectories until it is established as dominant historical view. To start a war is a difficult choice for any government. Governments are naturally interested in proving that their decision was right and that the threat they claimed led to the war existed and left them no other choice.

Free democratic societies curb some basic rights in times of war, but never all of them. For societies that place freedom of the press high on the agenda, efforts are certainly made by governments to win over the free press for their cause, but as a rule, there is no overt censorship or hard pressure on the media. Dictatorships use an external threat as justification for controlling the media so that a real war does not change the situation very much. One would expect, therefore, that press coverage of ongoing and past wars would reflect the character of politics in a specific country. Alas, empirical evidence shows that much more is involved than just unabashed censorship or pressure on the media to fall in line with their government’s cause. The second remarkable fact about media coverage of wars is that so little systematic empirical evidence has been collected. When it comes to the US-led war on Iraq, for example, there was no systematic investigation of the elite media until 2008. Gelb and Zelmati carried out a comprehensive study of what they termed “elite media” (e.g. New York Times (NYT), Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Time, and Newsweek) and arrived at the conclusion that the “ultimate centurions of our democracy” failed to live up to their critical function: “For the most part, the elite print press conveyed Administration pronouncements and rationale without much critical commentary.”[1]

It appears that when it comes to public opinion in times of war, the government’s job to convince the citizens is, as a rule, easy.[2]

The question as to why what may be the world’s freest and most independent press fell in line with a government which patently used subterfuge to get the blessing of democratic institutions and international organizations for its power projection schemes is controversial, but it may be reasonably explained by the shock which had gripped the US following 9/11. It is far more intriguing to observe the coverage of the Georgian war of such prestigious and critical press outlets as the New York Times and the Washington Post and ask: Have they learned from past mistakes?

In this respect, there are only partial investigations into the role of the media in the Georgian-Russian War. A comparison between the coverage of European and Russian media (print media and web blogs from Germany, Great Britain, and France) was conducted by Dennis Liechtenstein and Cordula Nietsch.[3] Roman Hummel interviewed journalists on the ground during the conflict. He found a striking difference between the “global players” who operate with enormous technical support and the “stand-alone war reporters.”[4]

Another question is who has “won” the media war on Georgia. Although most observers agree that the Western press initially accepted the Georgian government’s position, and became more critical only after some time, the consensus is that the Georgian government used the technical possibilities to spin public opinion more skillfully.[5] The Georgian government had hired its own PR firm, Aspect Consulting, which also works for Exxon Mobile, Kellogg’s, and Procter & Gamble. In addition, President Saakashvili has a background that includes a Columbia University education, familiarity with Western culture, and attempts to “pass” as a credible Western democrat. The Russian PR firms GPlus and Ketchum could not offset the combined effect of the Georgian president, who appeared as defending European values and was skillfully portrayed as a beacon of democracy.

The question who won the media war must not be confused with the quest for truth and the issue of legitimacy and justification. Facts are often high-jacked by perceptions, and there is always room for doubt. Nevertheless, it seems reasonably clear that the Georgian army started shelling Tskhinval[i] on the night of 7/8 July 2008, apparently before Russian regular troops crossed the Roki tunnel. According to documents that were leaked to Der Spiegel, a majority of the members of the EU’s independent international fact-finding mission (“Truth Commission”) arrived at the assessment that Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili started the war by attacking South Ossetia on 7 August 2008. This would refute Saakashvili’s claim that his country became the innocent victim of “Russian aggression” on that day.[6]

Whether the attack on Tskhinvali was a necessary response to the shelling of Georgian villages, and whether this was tolerated, aided and abetted, or simply not prevented by the Russian peacekeepers (which consisted of detachments of the regular 58th Army stationed in the region), and the degree to which the war was “planned” in Moscow beforehand, is an altogether different story. The EU “Truth Commission” will produce its own diplomatically smoothed version of the events leading up to the war.

This research project is not about the “true” facts. It seeks to draw conclusions from the way in which the war was covered by Russian, Georgian, and Western media. Specifically it seeks to identify the turning points that mark significant departures from previously used arguments and views. It took the Georgian opposition media a surprisingly short time to spell out openly that Georgia had suffered military defeat, and to turn against the president. On the surface, this would point to a sufficiently high degree of press freedom in a fledgling democracy. On the other hand, there is a deep distrust toward the media and politics as such, so that an infringement of the media space controlled by the government is not viewed as a serious threat. Georgian citizens have experienced a variety of governments and leadership personalities since the break-up of the Soviet Union and are used to changing narratives. Furthermore, the war was short and did not fundamentally change the status quo; the breakaway provinces Abkhazia and South Ossetia had been independent on a de facto basis for a long time. This certainly had not escaped the attention of the rank-and-file citizens, irrespective of officials’ spin version of events.[7] By contrast, the major Russian opposition paper, Novaya Gazeta, did not change its rather balanced view. In its first edition after the opening of hostilities, on 13 August 2008, Pavel Felgenhauer, the paper’s military expert, wrote, “This was no spontaneous, but a premeditated war.” He holds that the war started because of a joint South Ossetian-Russian provocation.[8]

Methodology

The investigation is based on a computer-assisted text analysis of the following press outlets:

- NYT

- Guardian

- Handelsblatt

- Der Standard

- Le Monde

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ)

- Washington Post

- Georgian Messenger

- Rossiiskaya Gazeta

- Novaya Gazeta

Between twenty and forty articles per press outlet were selected, resulting in a total of 371 articles. The selection was guided by the consideration that leading world press outlets should be included in the sample as well as papers representing the government and the opposition views in Russia and Georgia. Additionally, a sample of speeches and the declarations given by the Russian and the Georgian presidents were used to provide a blueprint of the official narrative. The time span covered was from 3 July to 30 December (2008). During this time, several reversals in opinions were identified.

The software used was SPSS. Simstat/wordstat 5.1 was used for control and external validation.

The key variables were as follows:

1. Source

2. Identifier

3. Date

4. Genre (article, commentary, other)

5. Status (pro-government, opposition, independent)

6. Style (balanced/biased, 10-point scale)

7. Assumed/Given Reasons For the War (Genocide, Protection of Citizens, Territorial Integrity, Protection of Democracy, Self-Defense, Preventive War, Peace & Security, International Law, Humanitarian Intervention, NATO enlargement, Pipelines)

8. Pro-Government Stance taken (10-point scale; for Western outlets – pro-Georgia)

9. Opposition (soft/medium/hard)

10. Aggressive tone (10-point scale)

11. Invectives (10-point scale)

The data were collected and analyzed by a joint Russia-Austrian working group.

The Official Narratives

Georgia

During the early stage of the war, President Saakashvili justified military operations thus:

· A necessary response to South Ossetian forces shelling Georgian villages, which led to the “liberation” of large swaths of South Ossetian territory by “Georgian law enforcement agencies;”

· The response to “large-scale aggression” by Russia;

· The Georgian resolve “not to give up its territories;”

· The defense of Georgian “freedom and sovereignty” (President Mikheil Saakashvili, Speech in Tbilisi, 8 Aug. 2008).[9]

Russia

President Medvedev gave the following justification:

· Response to “Georgian aggression against Russian peacekeepers and the civilian population in South Ossetia” and thus to a “gross violation of international law;”

· Prevention of a humanitarian catastrophe in South Ossetia;

· The protection of “the lives and the dignity of Russian citizens” in accordance with Russian legislation;

· The “punishment of the perpetrators” (President Dmitry Medvedev, Press Conference, Moscow, 8 Aug. 2008).[10]

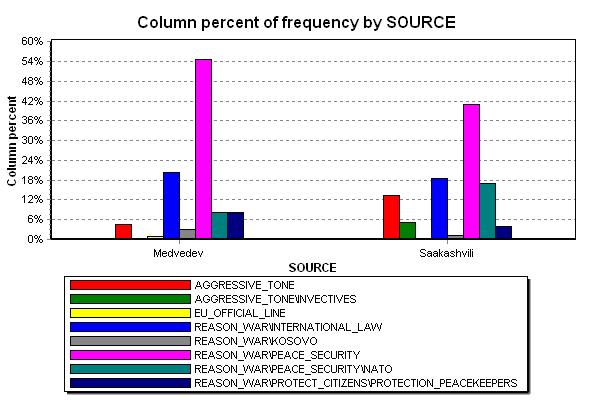

A content analysis (simstat/wordstat 5.1.) with all available and relevant official statements by both presidents, including speeches, press conferences, and interviews (number for Medvedev is 31; Saakashvili, 21), shows the differences in the rhetoric of both presidents.

Table 1[11]

| Medvedev | Saakashvili | |

| AGGRESSIVE_TONE | 4.6% | 13.2% |

| AGGRESSIVE_TONE\INVECTIVES | 5.3% | |

| EU_OFFICIAL_LINE | 1.0% | |

| REASON_WAR\ INTERNATIONAL_LAW | 20.4% | 18.4% |

| REASON_WAR\KOSOVO | 3.1% | 1.3% |

| REASON_WAR\ PEACE_SECURITY | 54.6% | 40.8% |

| REASON_WAR\PEACE_SECURITY\NATO | 8.2% | 17.1% |

| REASON_WAR\PROTECT_CITIZENS\PROTECTION_PEACEKEEPERS | 8.2% | 3.9% |

Unsurprisingly, both presidents justify the war with the necessity to re-establish peace and security. Saakashvili’s references to NATO imply that Georgian NATO membership would have prevented the war; Medvedev mentions NATO as a factor contributing to the tensions in the region (“regrettably, our proposals to conclude an agreement banning the use of force went unheard by NATO…”).[12] Since both are lawyers, there is a high frequency of references to international law. The Russian president chose a more moderate tone than his Georgian counterpart.

Comparison

General Results

Barring the results of in-depth and more detailed analysis, the picture of the media landscape is fairly distinct. While Western media can hardly be classified as pro-government and opposition, they nevertheless pursued a specific line at various points in time. Rossiiskaya Gazeta, a government-owned daily in Russia, stood out with its consistent pro-Russian line. The Georgian Messenger, though presenting an independent image, resembled a pro-government outlet with its anti-Russia orientation.

A straightforward comparison of means (“Pro-Georgian Orientation”), by and large, yields the expected results:

Table 2

| Source | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Median |

| NYT | 2.0833 | 24 | 3.33514 | .0000 |

| Standard | 4.3704 | 27 | 3.83454 | 4.0000 |

| Georgian Messenger | 5.2143 | 14 | 4.88606 | 6.0000 |

| Novaya Gazeta | 2.7692 | 13 | 3.58594 | .0000 |

| NZZ | 1.6667 | 27 | 2.96129 | .0000 |

| Washington Post | 4.4444 | 18 | 4.71820 | 3.0000 |

| Handelsblatt | 3.8000 | 25 | 3.97911 | 2.0000 |

| Guardian | 1.7308 | 26 | 3.31732 | .0000 |

| Rossiiskaya Gazeta | .0000 | 32 | .00000 | .0000 |

| Total | 2.6311 | 206 | 3.76632 | .0000 |

Conversely, the comparison of means for the variable “Pro-Russian Orientation” shows significant differences among the Western media. The Guardian led the list with a value of 3.4 on a 10-point scale. Der Standard appeared to pursue a fairly consistent anti-Russian line.[13] The standard deviations, especially of the variable “Pro-Georgian Orientation,” indicate a policy to print commentaries and reports across the ideological and attitudinal board. In order to capture the level of possible bias in favor of one or the other side, we used an indicator (“Media bias”) that is obtained by subtracting the values of the variables “Pro-Georgian Orientation” from “Pro-Russian Orientation.”

The results (Table 3) should reflect the degree to which an editorial policy of openness was realized. (Positive values suggest bias toward the Georgian side; negative values, a tendency to support the Russian side.)

Table 3 – Media_Bias

| Source | Mean | N | Std. Deviation |

| NYT | 1.0417 | 24 | 4.04839 |

| Standard | 3.7407 | 27 | 4.58755 |

| Georgian Messenger | 5.2143 | 14 | 4.88606 |

| Novaya Gazeta | 1.0000 | 13 | 5.90198 |

| Le Monde | 1.6429 | 14 | 4.71670 |

| NZZ | 0.1154 | 26 | 4.13112 |

| Washington Post | 3.2222 | 18 | 6.49484 |

| Handelsblatt | 3.5200 | 25 | 4.47325 |

| Guardian | -1.6923 | 26 | 5.66935 |

| Rossiiskaya Gazeta | -8.1875 | 32 | 3.61393 |

| Total | 0.3562 | 219 | 6.16970 |

Additionally, we used a variable that expressed the tendency or policy to take into account the standpoint of both sides (“Balance”).

A comparison of mean values (over a 10-point scale) produced the following results:

Table 4 – Balance (only commentaries and editorials)

| Source | Mean | N | Std. Deviation |

| NYT | 4.2083 | 24 | 3.45127 |

| Standard | 2.1852 | 27 | 2.46572 |

| Georgian Messenger | 1.4286 | 14 | 3.25137 |

| Novaya Gazeta | 3.7692 | 13 | 3.78932 |

| Le Monde | 7.1429 | 14 | 3.34795 |

| NZZ | 7.5556 | 27 | 3.16633 |

| Washington Post | 4.3333 | 18 | 4.53743 |

| Handelsblatt | 3.6154 | 26 | 3.53358 |

| Guardian | 4.9231 | 26 | 3.62130 |

| Rossiiskaya Gazeta | 0.8438 | 32 | 2.46406 |

| Total | 3.8914 | 221 | 3.89253 |

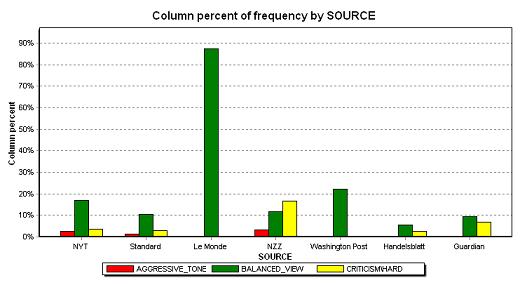

The high diversity of opinions in Western media is corroborated by the analysis of stylistic characteristics (simstat/wordstat).

Table 5

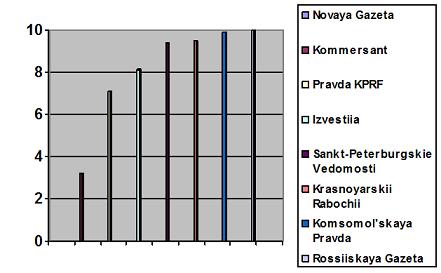

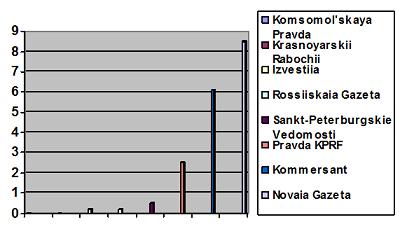

Overall, the analysis has produced evidence that there is a considerable amount of variation over the group that contains “Western media.” The same is true of Russian print media:

Table 6: Pro-Government Orientation (10-point scale)

Table 7: Degree of opposition to official gov’t line (10-point scale). Zero values are invisible.

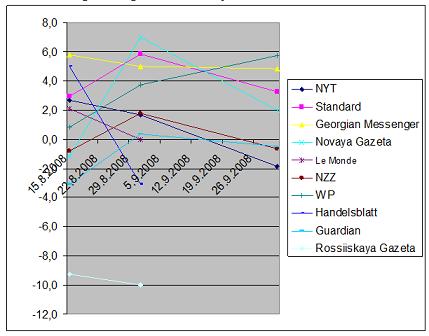

Variation Over Time

As the following table illustrates, only Rossiiskaya Gazeta showed a consistent coverage pattern over the four periods. The NYT started out moderately critical of Russia, changed to a distinct pro-Georgian attitude between 9 August and 15 August, and began to criticize the Georgian leadership after this point of time. Der Standard became more critical of Russia over the entire period in a linear fashion, which coincides with the pattern observed in the Novaya Gazeta. The Georgian Messenger became very critical of the Georgian government only at the beginning of September.

Table 8

| Source | Time_Period | Mean | N | Std. Deviation |

| NYT | July-15 Aug | 2.6923 | 13 | 4.21079 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 1.6667 | 3 | 5.03322 | |

| 1 Sept- | -1.8750 | 8 | 1.12599 | |

| Standard | July-15 Aug | 2.9375 | 16 | 4.93246 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 5.8571 | 7 | 3.84831 | |

| 1 Sept- | 3.2500 | 4 | 4.11299 | |

| Georgian Messenger | July-15 Aug | 5.8000 | 5 | 5.31037 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 5.0000 | 2 | 7.07107 | |

| 1 Sept- | 4.8571 | 7 | 4.91354 | |

| Novaya Gazeta | July-15 Aug | -1.1667 | 6 | 7.70498 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 7.0000 | 2 | 2.82843 | |

| 1 Sept- | 2.0000 | 3 | 2.00000 | |

| Le Monde | July-15 Aug | 2.0909 | 11 | 2.80908 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 0.0000 | 3 | 10.00000 | |

| NZZ | July-15 Aug | -0.8182 | 11 | 2.96034 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 1.7778 | 9 | 4.49382 | |

| 1 Sept- | -0.6667 | 6 | 5.27889 | |

| Washington Post | July-15 Aug | 0.8333 | 6 | 8.58875 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 3.7500 | 8 | 5.47070 | |

| 1 Sept- | 5.7500 | 4 | 5.05800 | |

| Handelsblatt | July-15 Aug | 3.0526 | 19 | 4.67230 |

| 16 Aug-31 Aug | 5.0000 | 6 | 3.74166 | |

| Guardian | July-15 Aug | -3.0714 | 14 | 5.22515 |

| July-15 Aug | 0.3333 | 6 | 6.25033 | |

| 1 Sept- | -0.5000 | 6 | 6.22093 | |

| Rossiiskaya Gazeta | July-15 Aug | -9.2800 | 25 | 2.01080 |

| July-15 Aug | -10.0000 | 3 | 0.00000 |

The Washington Post emerged as an outlier in terms of “Western” media due to the fact that it invited contributions by Georgia-friendly personalities such as Saakashvili and Robert Kagan.

Table 9 (Graphic Representation of Table 8)

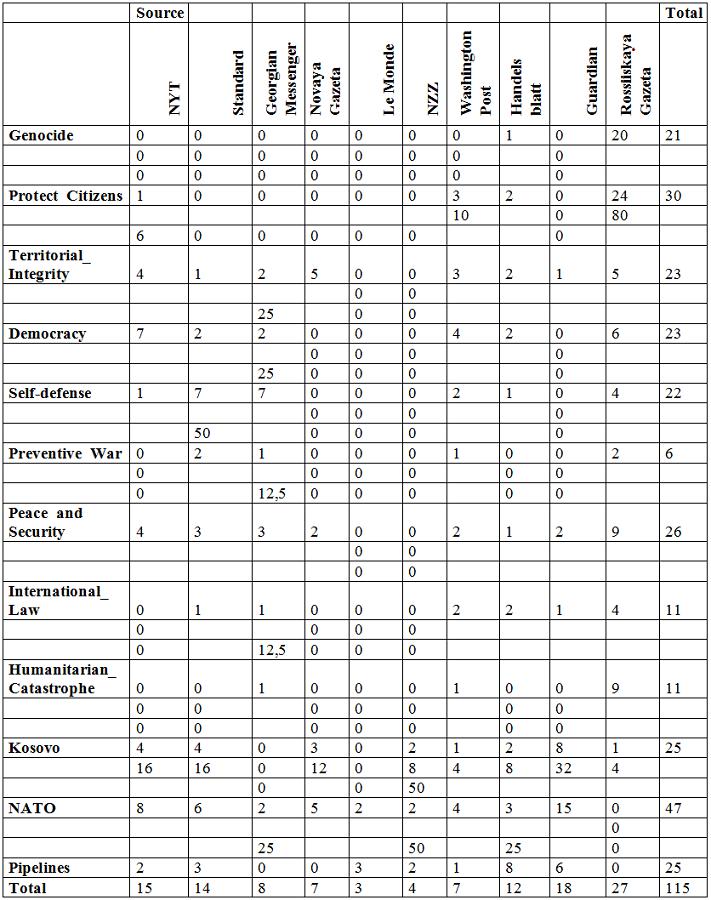

We also found a distinct variety of reasons mentioned to justify or to support the analysis of the war. The “loyal” media followed the official rhetoric rather closely (see appendix, Table 10).

Individual Print Media

The New York Times

This flagship of journalism in US, which trails in circulation only the USA Today and The Wall Street Journal and has a track record of fighting for free speech, took a clear position against what it perceived as the threat emanating from an aggressive Russia. While reports in general were balanced, commentaries minced no words to warn against Russia’s neo-imperialism. “The list of ways a more hostile Russia could cause problems for the United States extends far beyond Syria and the mountains of Georgia,” stated a commentator on 22 August 2008. “The gulag and the enslavement of wide swaths of Europe by the Soviet empire burden Moscow with a historical responsibility for the freedom of its neighbors,” stated another commentary on 1 September 2008. Nevertheless, a commentary published on 19 August held that “Russia did not want this war.” The NYT forcefully supported Georgia’s NATO membership: “At the NATO foreign ministers’ meeting in December, it should replace Bucharest blather with basics: a Membership Action Plan for Georgia and Ukraine” (20 Sept. 2008). The change in this stance only began in early November, when the paper began to “raise questions about the accuracy and honesty of Georgia’s insistence,” and noted that “Georgia’s actions in the conflict have come under increasing scrutiny” (5 Nov. 2008). This was seconded by critical comments on the state of the Georgian army, which showed a poor record during and after the war, despite massive US support and investments. Georgian military leaders were attested a “pure grasp of military intelligence” (17 Dec. 2008). Still, the well-grooved anti-Russia line was upheld: “Attempting to turn back the clock to the days when Moscow held uncontested sway” (20 Dec. 2008).

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Renowned for its conservative circumspection in reporting and its commitment to the ethical code of journalism, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, nevertheless, published lopsided commentaries. While it wryly remarked before the actual war: “Exclusively ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys’ cannot be identified … in this conflict” (3 July 2008), its first analysis of the war squarely attacked Russia: “The muscular remarks of the strongman Putin … are to justify the Russian excesses, which we recognize from Chechnya” (11 Aug. 2008).

However, Georgia was also criticized for good measure: “The Georgian government somehow still acts in a traditional voluntarist and Stalinist mind-set” (14 Aug. 2008).

Another commentator was forcefully in favor of NATO enlargement: “A hardened stance is the only logical option, and it includes a clear vote for NATO membership” (16 Aug. 2008). Another writer criticized the West for its “subservient tolerance in the face of the Russian power drive” (16 Sept. 2008).

Der Standard

This left-liberal Austrian daily invited commentators from across the ideological board, and is read primarily by the white-collar class. Nevertheless, there is a clear tendency to criticize what is viewed by commentators and analysts as “Russian neo-imperialism” in tandem with pronounced anti-NATO attitudes: “In South Ossetia the stakes are no less than the defense against a post-soviet imperialism” (9 Aug. 2008); “Provocative strategy of Russia” (11 Aug. 2008); “Moscow wants the subjection of the former Soviet republic” (11 Aug. 2008); “Russian imperialism is re-emerging” (16 Aug. 2008).

Other statements included: “… revanchist, revisionist Russia whose conduct reminds us of the Soviet Union” (16 Aug. 2008); “The Baltic states and Ukraine will be the next” (16 Aug. 2008); “Saakashvili’s US advisors had their fingers in the pie” (22 Aug. 2008); and “EU provides better conditions for security and stability than NATO” (19 Sept. 2008).

There were, of course, also critical voices against the Georgian leadership: “The coup in South Ossetia turned out to be a catastrophe; what made Saakashvili risk this cliff-hanger?” (14 Aug. 2008).

The Georgian Messenger

This periodical claims to be independent and self-financed. Nevertheless, the anti-Russian attitude and the support for the Georgian leadership’s foreign policy were clear and consistent: “Hitler was not stopped in the years leading up to World War II” (28 Aug. 2008); “The best way to avoid this would be if Ukraine joined NATO immediately” (8 Aug. 2008); “According to a Georgian folk tale, the cruel giant has many heads. The hero has to behead them all, one by one” (12 Aug. 2008); “Putin the Terrible” (15 Aug. 2008); and “… the Kremlin’s criminal duet” (28 Aug. 2008).

Only after the first critical voices appeared in Western media, the military defeat was openly admitted and the issue of political responsibility addressed: “… these only highlight the scale of the defeat Tbilisi has suffered” (15 Aug. 2008).

The Guardian

The coverage of the British daily was characterized all along by the attempt at conveying the interests of all sides and at presenting a balanced view. Early in the conflict, on 8 August, a background analysis was published which elucidated the positions of both parties. Following the escalation, on 9 August, a commentary warned against blaming Russia alone for the war out of a “cold war reflex” and engaging in inappropriate comparisons such as Prague 1968 (e.g. “Not every development in the former Soviet Union is a replay of Soviet history”). The commentary clarified that the South Ossetian population expected protection against ethnic cleansing from the Russian troops. President Saakashvili’s democratic conduct is called into question, as was the legitimacy of the drive to arm regions in Russia’s backyard. Saakashvili’s assumption that NATO would come to his help was classified as a strategic mistake of the Georgian president which has undermined his credibility. References to the West’s double standards, which implied the different approach taken in the Balkans, were also criticized.

There were also contributions that criticized Russian conduct. On 12 August, an author accused Russia of threatening European democracy so as to provoke Europe and to test its malleability. The article was a call to support Georgia against Russia. Other articles attacked Europe for leaving Georgia in a bind by not promoting its NATO integration. Another author writing in the same edition criticized Saakashvili for his rhetoric and for portraying himself as a victim, thus denying the authoritarian features of his rule.

An article on 16 August warned of the “Finlandization” of Georgia by Russia and interpreted the Russian campaign as retaliation for Kosovo. This article was set off by one (20 August) which lambasted NATO as “useless.” Russia’s feeling of being provoked by the organization was deemed justified. In a similar vein, a 9 September commentary criticized the knee-jerk Western support for any country which opposes Russia.

Generally, the Guardian provided room for a broad spectrum of opinions. Authors of different ilk and positions were given equal possibilities. A distinct and consequential policy stance could hardly be identified.

Washington Post

A favorite print medium of US liberals, the Washington Post is known for its pluralist and tolerant attitude toward dissenting opinions. Among its staff writers are authors spanning the ideological and partisan board. In its coverage of the war, it published commentaries by Saakashvili and Gorbachev. Nevertheless, commentators who oppose Russia were dominant, which explains the relatively high Media Bias value. Examples included: “This war did not begin because of a miscalculation by Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili. It is a war that Moscow has been attempting to provoke for some time” (Kagan, 11 Aug. 2008); “If the international community allows Russia to crush our democratic, independent state, it will be giving carte blanche to authoritarian governments everywhere. Russia intends to destroy not just a country but an idea” (Saakashvili, 14 Aug. 2008); “The threat to Georgia, Russia’s other democratic neighbors and America ultimately arises from a lack of democracy within Russia” (Sharansky, 14 Sept. 2008); “We view the events as confirmation of the dangerous challenge posed by an authoritarian regime unwilling to recognize the sovereignty of its former imperial possessions” (16 Aug. 2008); “The West spent a good part of the past 17 years worrying about Russia’s dignity – expanding the Group of Seven industrial nations to the G-8, for example – and it’s not clear such therapy had any effect” (17 Aug. 2008); and “Russia’s invasion of Georgia was a highly organized assault that now appears to have been planned for months” (19 Aug. 2008).

On the other hand, Gorbachev (12 Aug. 2008) wrote, “The Georgian military attacked the South Ossetian capital of Tskhinvali with multiple rocket launchers designed to devastate large areas. Russia had to respond.” Another article stated: “Some Western diplomats now privately say that the Georgian leadership or military made a serious and possibly criminal mistake last week by launching a massive barrage against the South Ossetian capital of Tskhinvali, which inevitably led to major civilian deaths and casualties” (13 Aug. 2008).

Handelsblatt

Handelsblatt is the leading German economic daily. It represents corporate interests and cooperates closely with the Dow Jones Edition. This is illustrated by its coverage of the war, which was slanted toward the Georgian standpoint: “The Georgian military operations provided a pretext for Putin to hone his legacy” (12 Aug. 2008), and “[Putin] wants to re-establish Russia’s traditional zone of influence” (13 Aug. 2008).

Sometimes the blame was put on both sides, for instance: “Russia has profited from the opportunity that Georgia’s silly offensive gave her” (15 Aug. 2008). Or it was put squarely on the Georgian president: “A firebrand like Saakashvili” (11 Aug. 2008), and “Georgia’s future president should not be such an unguided missile as Saakashvili” (17 Aug. 2008).

Analyzing the power structures in Russia also served as a tool to shift the blame on Russia: “Putin and Medvedev: ‘Good cop-bad cop’ ” (12 Aug. 2008).

Le Monde

Le Monde has a left-liberal orientation which combines the anti-Soviet and anti-American heritage of the French left-wing with its ethics of promoting enlightenment. While the first articles that covered the conflict were strictly factual and balanced, commentaries minced no words in unmasking the truth behind the war: “This is Moscow’s revenge … the preventive war” (12 Aug. 2008); “A more aggressive Russia is a menace for European energy security” (13 Aug. 2008); “Putin’s aggression against Georgia” (16 Aug. 2008); and “Faced with Moscow’s will to annex Georgia, the Europeans exhibit an absurd paralysis which they must shed” (21 Aug. 2008).

Some commentaries, however, took the opposite position: “The Cold War – a misleading analogy” (14 Aug. 2008), and “The convenient image of a poor little Caucasian republic oppressed by its huge neighbor does not hold in the face of the facts” (22 Aug. 2008).

Rossiskaya Gazeta

Rossiiskaya Gazeta had a pronounced and consistent pro-Russian line, which echoed the style and the content of official statements: “Saakashvili turned rapidly … from a unifier of Georgian territories to the grave-digger of Georgian statehood” (9 Aug. 2008); “The US thinks that if they turn the Caucasus into a powder keg, they strengthen their influence in the region and decrease that of Russia” (12 Aug. 2008); “Saakashvili was betting on a blitzkrieg” (13 Aug. 2008); and “Saakashvili’s criminal policies” (15 Aug. 2008).

However, it criticized the Russian government for its passivity in the propaganda war: “There were no Russian statements in the leading channels of the world for two days” (11 Aug. 2008). In this context, the preponderance of Western media was deplored: “Many Western channels have become the mouthpiece of Georgia’s bellicose propaganda” (20 Aug. 2008), and “When the Russian troops struck back, the US state agitprop engaged in a storm of outrage” (22 Aug. 2008).

Another point of criticism was the apparent unpreparedness of the Russian army: “Why did the war … take us by surprise?” (21 Aug. 2008).

Novaya Gazeta

This well-known opposition paper (owned by former president Gorbachev and the businessman Lebedev) offered a broad spectrum of opinions on the war. Saakashvili was criticized along with the Russian government: “… such politics is nothing but adventurism” (11 Aug. 2008), and “This is a Georgian crime; the Russian crime was invading the territory of a sovereign state.”

Frequently, contributors conjured up the grave consequences of the military campaign for Russia: “Palestinization of the Caucasus” (25 Aug. 2008), and “The awakening of our daydreamers may be rather rude” (5 Sept. 2008).

Conclusion

In their coverage of the Russia-Georgia war, the print media under analysis showed a wide range of patterns. The Georgian Messenger and the government-run Rossiiskaya Gazeta were very closely in line with the official stance and the rhetoric of the Georgian and Russian presidents, respectively. Critical contributions were published after some delay and concerned the insufficient preparations (Rossiiskaya Gazeta) or the fact that the decision to attack South Ossetia was made by a small group of people without broader consultations (Georgian Messenger). Russia’s leading opposition paper, Novaya Gazeta, criticized the Russian government harshly for having provoked the war and for its negligence in preparing the army for it.

European and US media generally provided room for various opinions. Nevertheless, a majority of commentaries published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Handelsblatt, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Le Monde, and Der Standard showed a preference for the Georgian standpoint, while the Guardian was predominantly critical of it.

Unlike the coverage of the Iraq war, there was no split between European and US media. Media “spin” by both warring governments produced only negligible effects.

Appendix

Declaration of Universal Mobilization by Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili:

“My dear fellow citizens, I would like to brief you about the events that took place last night. As you all know, we initiated military operations after separatist rebels in South Ossetia bombed Tamarasheni and other villages under our control. Most of the territory of South Ossetia has been liberated and is now under the control of Georgian law enforcement agencies. Last night, Georgian law enforcement agencies liberated the Tsinagra region, the Znauri region, the village of Dmenisi (one of the biggest village in the region), Gormi, and Xetagurovo. They also have surrounded Tskhinvali, most of which has been liberated. As I speak, fighting is taking place in the city center. The fighting was initiated by the separatist regime. Aircraft entered Georgian airspace from the territory of the Russian Federation and the attack was carried out from the North. I also would like to address the international community. A large-scale military aggression is taking place against Georgia. Over the past few minutes and hours, Russia has been bombing our territory and our urban areas. This can only be described as a classic international aggression. I would like to address the Russian Federation. Cease your bombardment of peaceful Georgian towns immediately. Georgia did not seek confrontation. Georgia was not the aggressor, and Georgia will not give up its territories. Georgia will not renounce its freedom and sovereignty. We have mobilized tens of thousands of reserve officers, and the mobilization process continues. We all have to unite in this very important and difficult moment for our homeland, when our future and our freedom are under threat-when others are trying to hijack our future and our liberty. We all have to unite. We should not be afraid. We should not be afraid of their bombs, of their attacks, of their aggression – we are stronger than that. This is our homeland. We are defending our country, our home. Georgia-and we are defending Georgia’s future. We must unite. All of us, hundreds of thousands of Georgians here and abroad, should come together, unite, and fight to save Georgia. We are a freedom-loving people, and if our nation is united, no aggressor will be able to harm it. We will not give up, and we will achieve victory. I call on everyone to mobilize. I declare, here and now, a universal mobilization of the nation and the Republic of Georgia. I hereby announce that reserve officers are called up-everyone must come to mobilization centres and fight to save our country. We will prevail, because we are fighting for our homeland, our Georgia. If we stand together, there is no force that can defeat Georgia, defeat freedom, defeat a nation striving for freedom-no matter how many planes, tanks, and missiles they use against us. Long live Georgia, and may God save her and all of us.”[14]

Statement on the Situation in South Ossetia by President Dmitriy Medvedev:

“As you know, Russia has maintained and continues to maintain a presence on Georgian territory on an absolutely lawful basis, carrying out its peacekeeping mission in accordance with the agreements concluded. We have always considered maintaining the peace to be our paramount task. Russia has historically been a guarantor for the security of the peoples of the Caucasus, and this remains true today. Last night, Georgian troops committed what amounts to an act of aggression against Russian peacekeepers and the civilian population in South Ossetia. What took place is a gross violation of international law and of the mandates that the international community gave Russia as a partner in the peace process. Georgia’s acts have caused loss of life, including among Russian peacekeepers. The situation reached the point where Georgian peacekeepers opened fire on the Russian peacekeepers with whom they are supposed to work together to carry out their mission of maintaining peace in this region. Civilians, women, children and old people, are dying today in South Ossetia, and the majority of them are citizens of the Russian Federation. In accordance with the Constitution and the federal laws, as President of the Russian Federation it is my duty to protect the lives and dignity of Russian citizens wherever they may be. It is these circumstances that dictate the steps we will take now. We will not allow the deaths of our fellow citizens to go unpunished. The perpetrators will receive the punishment they deserve.”[15]

Table 10 – Reasons for the War (covering three time periods in 2008: July-15 Aug., 16 Aug.-31.Aug., 1 Sep.- )

This investigation is the product of an institutional partnership between the Russian Institute (Russkii Institut, Moscow) and the International Center for Advanced and Comparative EU Russia/NIS Research, Vienna, and pursues no political agenda. The teams were coordinated by H.G. Heinrich and K. Tanaev, respectively. The present paper is an interim report, since in-depth analysis and additional analytical work, including a Georgian team, is under way.

[1] Leslie H. Gelb & Jeanne Paloma-Zelmati, “Mission Not Accomplished,” Democracy,

vol. 13 (2009), http://www.democracyjournal.org/archive_author.php (accessed June 23, 2009).

[2] A recent opinion poll (GORBI, Tbilisi) found low confidence ratings for Russian president Medvedev (8% trust). Merab Pachulia, “Poll Results: New Realities of Geopolitics and Political Staying Power,” The Georgian Times, June 29, 2008. In Russia, president Medvedev is consistently supported by over 70% of respondents (Levada Centre, June 2009; http://www.levada.ru/press/2009062503.html, (accessed July 20, 2008).

[3] Dennis Liechtenstein & Cordula Nietsch, “Framing the Caucasian War – A Content Analysis of the Media Coverage in Europe and Russia,” (abstract, War, Media, and the Public Sphere, Int’l Symposium of the Austrian Academy of Sciences & the Univ. of Klagenfurt, Vienna 5-7 March 2009), http://www.oeaw.ac.at/cmc/wmps/abstracts (accessed May 20, 2009). The media strategies were addressed in Roger Boyes & Tony Halpin, “Georgia loses the fight with Russia, but manages to win the PR war,” Times Online, August 13, 2008, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article4518254.ece (accessed May 20, 2009), and BBC News, “Russia-Georgia media war escalates,” September 29, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/5392058.stm .

[4] Roman Hummel, “Limits of Journalism in War Situations. A Case Study From Georgia”, September 2008, http://www.oeaw.ac.at/cmc/wmps/pdf/hummel.pdf, (accessed 28 July 2009) .

[5] Peter Wilby, “Georgia has won the PR War,” The Guardian, August 18, 2008.

[6] The chairman of this Commission, Ambassador Heidi Tagliavini, has distanced herself from these allegations and referred to the final conclusions to be published at the end of July viz. Nov. 2009. See Zerschmetteter Traum [Shattered dream], Der Spiegel, No. 25 (June 15, 2009).

[7] Lela Yakobishvili & Zaza Piralishvili, Kartuli politikis theatraluri dialektika. Tserili kartuli identobaze [The Theatrical Dialectics of Georgian Politics. Writings on Georgian Identity] (CISS, Tbilisi, 2007), 108.

[8] Pavel Felgenhauer, “Schem Gruzia podoshla k voine” [How Georgia prepared for the War], Novaya Gazeta, August 11, 2008. Needless to say, this is Mr. Felgenhauer’s personal opinion.

[9] For the full text, see appendix.

[10] For the full text, see appendix.

[11] All tables in this paper have been generated by the authors.

[12] Statement by President Dmitriy Medvedev, Moscow, Aug. 26, 2008, http://www.kremlin.ru/eng/speeches/2008/08/26/1543_type82912_205752.shtml (accessed June 20, 2008).

[13] In all cases, the results are highly significant (α = .000).

[14] Declaration of Universal Mobilization by Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili, Tbilisi, 8 Aug, 2008, http://www.president.gov.ge, (accessed 23 June 2008).

[15] President Dmitry Medvedev, Statement on the Situation in South Ossetia, Moscow, 8 Aug. 2008; http://www.kremlin.ru/eng/speeches/2008/08/08/1553, (accessed 23 June 2008).