Marco Giuli is a researcher at the Brussels-based Madariaga – College of Europe Foundation. His area of research covers EU-Russia relations, energy security, and international energy markets.

Abstract

This paper analyses the potential effects that the systemic developments stemming from the global financial crisis and the August war are likely to have in Georgia, within a context of hegemonic stability theoretical fundamentals. According to this perspective, both events have undermined the role of the US as the sole world hegemon. As a result, the Western strategic priorities toward the Caucasus are likely to shift, to the detriment of the special relationship between the Saakashvili administration and the US. To demonstrate this, the analysis will focus on the case study provided by energy- and transit-related Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), as the Georgian political and economic dependence on a geopolitical rent is strongly connected to them and is likely to disappear in the aftermath of the recent events.

Keywords: Georgia, Financial crisis, Russia, War, Hegemony, Nabucco, FDI

Introduction

The Russia-Georgia war of August 2008 and the sudden acceleration of the global financial crisis are considerably affecting Georgia’s international position and its economy. A reconsideration of Georgia’s international position is needed because of its strong relationship with the US – considered here as a “declining hegemon” within the current system of international relations – and the huge impact of this relationship on Georgian capital inflows.

The first section will focus on the political effects of the combination of the two crises on Georgia. The interconnectedness between the two events will be explored in the light of the theoretical framework provided by the hegemonic stability theory. In this respect, the impact of the August war and the credit crunch on the perceived ability of the US to provide international public goods, allowing the current “unipolar” international system to work, will be briefly described. This description will place the evolution of Georgia’s international position into a context characterized by the likelihood of the hegemon’s progressive disengagement from the Caucasus, aiming to reallocate political and physical

resources towards issues widely considered as more urgent. Several examples of such an evolution will be provided by taking into consideration the recent developments concerning the issue of the Euro-Atlantic institutions enlargement.

The second section will describe the economic impact of the financial crisis on Georgia. This issue will be approached by comparing the fundamentals of the Georgian economy to the other Former Soviet Union (FSU) countries that are experiencing financial turbulence. This approach will allow for deciphering, despite some basic differences, how Georgia may suffer the same outcomes because of peculiar imbalances connected to strong dependence on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and to an underdeveloped industrial base, which is undermined by a version of the so-called Dutch disease that has to do with the specific political stance of the country on the international stage.

Finally, the third issue will provide a case study of the combined political and economic effects of the August war and the financial crisis by addressing energy-related investments. It is necessary to evaluate whether the Georgian “geographical rent,” due to its status of being the sole transit corridor for Western-backed diversification projects, will continue to be profitable, given both the new US Administration’s supposed need to re-engage Russia and falling hydrocarbon prices, which may reduce the prospects for expensive investments.

Georgia and the Systemic Crisis: A Hegemonic Stability Perspective

The aim of this section is to figure out the interrelation between the August war and the global financial crisis to explore its political impact on Georgia. The context will be framed according to the theoretical perspective provided by the hegemonic stability, since both events are seen as signs of the crisis of the role of the US as the sole world hegemon. This view has been widely suggested by the Russian rhetoric according to a traditional approach to the international relations.[1] Apart from political provocations, the two events seem to have something to do with each other in fostering the downsizing of the US power within the international system so that Georgia will unavoidably be affected by the consequences of these developments because of the widely recognized support provided by Washington to the Georgian re-positioning within the international stage in the aftermath of the Rose Revolution of 2003.

The hegemonic stability theory dates back to the work of Charles Kindleberger about the Great Depression. According to his study, for an international system of trade and finance to work smoothly there must be a hegemon.[2] This happens due to the fact that there is a collective action problem in the provision, regulation, and institutionalization of trade and finance-related public goods, such as well-defined property rights, common standards of measures including an international reserve currency, consistent macroeconomic policies, proper actions in case of economic crises, and stabilized exchange rates. The collective action problem stems from the fact that these collective goods are international public goods to the extent that they are non-excludable – others can benefit from these goods, even if they do not contribute to providing them – and non-rival: one actor’s use of the good does not seriously decrease the amount available to the others. As a result, the presence of a hegemon is the solution to this collective action problem, since, given the anarchic nature of the international system, no one would procure gains from providing public goods without enjoying a dominant position within the system.[3] In other words, the aforementioned public goods are ensured by a state holding a technological advantage, desiring an open trading and financial system to penetrate new markets. To ensure these public goods, according to Keohane, the hegemon needs to possess the ability to create and enforce international norms, the willingness to do so, and decisive economic, technological, and military dominance.[4] This last feature can be considered as the necessary tool to enforce the international norms upon which the hegemony relies. Nye explored common characteristics of hegemons, stressing that they have a structural power at their disposal, termed as soft power, through which the hegemon has the ability to shape other states’ preferences and interests.[5] This implies that the need to mobilize the raw power resources a hegemon has at its disposal in a direct and coercive manner means a weakening – or a crisis – of the hegemony.[6] This theory can be classified as belonging to the realist tradition because of its focus on the importance of power structures in international relations. In other terms, a realist interpretation of the hegemonic stability theory allows for interpreting the institutions of globalization as a tool aimed at preserving US hegemony and the integrity of the unipolar order that emerged after the collapse of communism. Nevertheless, power alone cannot explain the reason why the other actors sometimes acquiesce to one hegemon while opposing another. The hegemonic stability has to be integrated by the concept of legitimacy, referring to the perceived justice of the international system. In sum, to be stable, hegemony needs all three criteria identified by Keohane – plus legitimacy.

But how does hegemony decline? The debate about the hegemonic decline focuses on both domestic and external reasons: the cost of defending the system militarily could rise excessively to national savings and productive investments; the hegemon becomes frustrated with the “free-riders” enjoying more gains than it does; or more efficient, dynamic, and competitive economies rise, undermining the hegemon’s international position. In crude realist terms, the actors will accept the dominance as long as the hegemon maintains a preponderance of power, as challenging it means running the risk of retaliation.[7] According to the said theoretical criteria, the August war and the global financial crisis undermined the US hegemony, as far as both power and legitimacy are concerned, to the extent that the hegemon’s might and the willingness to use it is no longer perceived by the system’s other actors as a deterrent, while the international financial architecture is no longer perceived as fair.

The Caucasus war demonstrated that for the first time after the emergence of the “unipolar moment”[8] in the early 1990s, Russia – considered as a great power, according to Buzan’s classification[9] – has been able to use force beyond its borders without fear of retaliation by the hegemonic power. Since a hegemon must have the capability to enforce the rules of the system, the willingness to do so, and decisive economic, technological, and military dominance, the Caucasus war cast a huge shadow over the US ability to exert the structural power that makes the hegemon able to shape other actors’ preferences and interests,[10] as far as the first two criteria are concerned. The Russian reaction, a deep military penetration into the territory of a close ally of the hegemon, clearly reflects a strong belief that the dominant power is no longer able to underwrite the rising costs of the hegemony, with empirical evidence showing that these costs escalate, reducing the hegemon’s surplus.[11] In this case, the preferences of a great power have not been influenced at all by the evident hostility of the hegemon to such a move. Indeed, the idea of a declining hegemony due to its rising costs described as an “imperial overstretch” has been in use since the late 1980s.[12] More recently, several scholars identified the crisis of the unipolar moment, led by the American global power with the Bush Administration’s switch to a unilateralism, which turned out to undermine the multilateral pillars of globalization upon which the US hegemony relied.[13] In this regard, the weakening of institutions such as the UN – and paradoxically, even NATO – coming from the US strategy against transnational terrorism in the aftermath of September 11 has been widely considered as the end of soft power and the beginning of an imperial attitude, naturally leading into a crisis of hegemony. But even if the concept of the falling hegemony has been around for the last two decades, the Russo-Georgian war has a fundamental meaning as a linchpin of the decay of the American primacy within the international system.

A reading of the August events in the Caucasus as a turning point for the imperial overstretching process because of the Russian use of force abroad is enhanced by the presence of another episode implying a systemic effect in terms of hegemony crisis: the global financial downturn. According to many scholars and commentators, the current crisis is an existential threat to US hegemony in that it unveiled the unsustainability of a world financial architecture suited to ensuring the American leading role. According to the early formulation of the hegemonic stability theory, the financial crisis could be interpreted as the outcome of the growing mistrust in the US ability to provide international public goods that allow the current international system of trade and finance to function. This mistrust is basically due to the specific nature of the collapse, widely described as the result of the interaction between the external imbalances of the US economy[14] and the bursting of the housing bubble. The manifestation of the hegemony crisis lies in the need to revise the US strategy of growth without savings, a strategy that allows it to play a hegemonic role by relying on the outsourcing of the financial resources necessary to provide international public goods. As a result of this unavoidable revision, the forthcoming years could witness a shift to increasing multipolarity due to the growing significance of the emerging powers’ role in rewriting the institutional structure of global capitalism.

Is this mistrust – potentially leading to a shift of the global distribution of power – based only on the perception of a bad macroeconomic management of the system on the part of the hegemon? According to this brief introduction of the two crises, they seem to show the emerging hegemon’s inability to provide security and financial stability. As the hegemonic stability theory historically assumes that for an international system of trade and finance to work properly, there must be a hegemon, it can be surmised that there is an interrelation between the war and the financial crisis: the war demonstrated that certain public goods, such as the preservation of the system from some other great power’s revisionist attitude,[15] can no longer be provided by the hegemon’s deterrence, already under the strain of two ongoing wars. To this extent, it might have contributed to the acceleration of the crisis by fostering mistrust. One could underline the fact that by analyzing the stock market trends on monthly basis, the reactivity of the international stock market indexes to the Caucasus events has been much more impressive than the reactivity of the single Russian indexes.[16] Of course, this does not provide any evidence, but the fact that military might (a hegemon’s tool to ensure the international security as a public good in order to allow international markets to work) is considered by the rating agencies as a component to assess the US debt solvability[17] should enforce this view. Thus, the systemic dimension of the Caucasus war, highlighting the impossibility of preventing a great power from using the force abroad – notably against a close hegemon’s ally – cast a shadow over the US military factor as a last resort to ensure a sound international environment for the system of trade and finance.

What are the consequences, then, for Georgia? Of course, the given systemic impact of the financial crisis does not suit the Georgian elite, because a weakened US could decide to disengage (totally or partially) from the Caucasus. Many Georgian analysts are showing considerable concerns in their speculations about the Caucasian policy likely to be undertaken by the Obama Administration, stressing that it is supposed to defuse tensions around the world – including the difficult US-Russia relationship – by withdrawing from some international military and diplomatic battles. Despite emphasis on the likelihood of persisting preferential relations with the US,[18] Georgian commentators are unanimous in admitting that Georgia will have to follow suit in the approach of the new US leaders by softening Saakashvili’s tough foreign policy line vis-à-vis Russia. The strong links developed by the Georgian officials with Republican candidate John McCain demonstrated Tbilisi’s preference for a confrontational approach toward Moscow, shown by the assertive McCain’s calls for isolating Russia by suspending its G8 membership. Some events may be considered as proof that Georgian commentators are right irrespective of the previous or current US Administration. Between the 2nd and 3rd of December 2008, both the EU and NATO kept Georgia at bay. The EU offered to strengthen cooperation but avoided any reference to membership. Georgia was included in a group of Eastern neighbors (Eastern Partnership Initiative – EaP) with no mention of the August war. The EaP, which is supposed to go beyond the traditional European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), implied the introduction of Association Agreements (AA) as the contractual framework for stronger engagement, without reference to membership.[19] As far as NATO is concerned, the Membership Action Plan (MAP) for Georgia was denied during the December summit in Brussels. The Ministers concluded that “both Georgia and Ukraine have made strides forwards but both have significant work left to do.”[20] At the same time in Nice, the EU restarted the EU-Russia negotiations launched in Khantiy Mansiysk before the August war, whilst the NATO-Russia dialogue has been fully restored.

These events can be interpreted as an outcome of the two crises on the systemic level, with Georgia finding itself in a very weak position. The first steps of the Obama Administration on this issue suggest that the importance of NATO enlargement towards the FSU will be scaled back. If we assume the financial crisis as depriving the US hegemony of a considerable degree of legitimacy and capabilities, a predictable approach will be to withdraw from a front (the Caspian basin) whose importance will be necessarily downgraded by the global developments of the last months of 2008, even in the light of the impact of the financial crisis on the energy markets that will be explored in the third section. Perhaps the US will finally get rid of the inconsistencies of the Clinton policy (“Russia first”, but attempting to separate the destiny of the other FSU countries from the influence of Moscow mainly through the diversification of energy routes) and the Bush policy[21] (requiring the FSU countries’ cooperation to fight terrorism, but attempting at the same time to undermine their authoritarian regimes) by looking to restore a sound relationship with Russia, which is needed to tackle issues such as Iran and Afghanistan, perceived by the US as much more urgent than the Caucasus. Though the latest visit of Vice President Joe Biden to Georgia served to underline the policy of continuing to support Georgia, it seems that the US attitude toward its domestic problems will be rather different from the one shown by the previous Administration. For instance, Biden made clear that there will be no military way to reassert control over Abkhazia and South Ossetia, giving the impression that the current Administration is not going to give an unconditioned endorsement to Saakashvili’s future decisions in this regard.[22] Such a development is definitely undesirable for the Georgian government.

After this brief description of the systemic implications of the financial crisis for Georgia, it is possible to assess the economic impact on the country in the light of its critical and politically controversial integration in the global economy. The peculiarities of this integration and notably the Georgian dependence on foreign capital inflows widely mirror the relevance of the political rent from which Georgia has benefited so far due to the Western geopolitical priorities in the region.

Georgian Economy in the Midst of Turbulence

The financial crisis raised concerns about several transitional economies, notably in the FSU. The Kazakh economy, for instance, began to suffer in the summer of 2007 in the aftermath of the US subprime crisis, which heavily affected the Kazakh real estate sector and turned into a proper banking crisis in 2008 as a result of the overexposure to the construction sector. Foreign borrowings, half of which came from US banks involved in hedge funds, led the foreign debt to reach 42% of Kazakh exports.[23] In Ukraine the impact has been even worse due not only to the banks’ exposure to the “bubbling” real estate sector but also to the collapse of the global demand for steel. After the drain of 3 billion USD from the Central Bank foreign reserves to defend the local currency, the IMF arranged an emergency package of 16.5 billion USD,[24] the size of which was impressive compared to the Ukrainian economy and provides some information about the degree of concern, widespread among the financial institutions as far as the impact of the crisis on the FSU is concerned.[25] Even in Russia[26] the crisis was displaying its effects: foreign reserves were dwindling at a rate of 22 billion USD per week, slumping from the peak level of 597 billion USD in August to 453 billion USD at the end of November,[27] leaving the authorities with the choice between draining the reserves further still or letting the currency float freely with a considerable risk of overshooting.

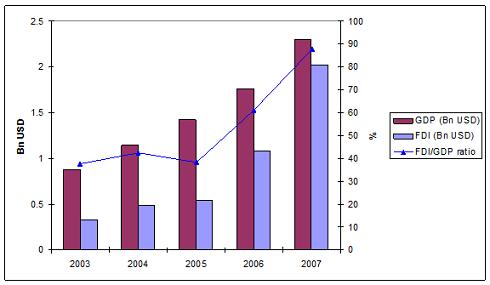

The case of Georgia seems to be rather different, which leaves ample room for debate among optimists and pessimists. According to experts, the Georgian real estate market is not significantly exposed to international turbulence, as the main players have limited access to the world capital and debt market. Hence, the backwardness of the Georgian banking sector is turning out to be, ironically, its saving grace. Further, some insist that the distance from the US, considered as the crisis’s epicenter, means that trade volumes between the two countries are too limited for any potential consequences resulting from an US recession.[28] Unfortunately this is only one part of the story. The Georgian economy is considerably different from many other CIS countries as it is not that dependent on natural resources, but this means that there are different fragilities likely to emerge under the strain of the global financial crisis. In the aftermath of the Rose Revolution (2003), many commentators celebrated the impressive economic performance of the country’s new leadership, which comprises a shocking reform agenda focused on the removal of bureaucratic barriers, as well as lowering taxes and properly collecting them. With growth rates peaking during the last two years between 10% and 12%, both the authorities and financial institutions were right in describing the country as a success story for neoliberal “orthodox” reformism. Nevertheless, a closer look at the fundamentals reveals some considerable imbalances that emerged during these bright years, which may create severe problems as the global financial crisis casts its shadow on the prospects for growth. Most of the concerns are raised by the excessive Georgian dependence on FDI, which has been the main growth component during the last five years. Figure 1 shows that private foreign investments, massive private donors’ outlays, and foreign aid made capital net inflows account for 88% of GDP in 2007. This data is not shocking; it makes Georgia an outlier with respect to the CIS countries’ average net capital inflows, which accounted for 9.6% of CIS GDP in 2007.[29]

Fig. 1: FDI net inflows in Georgia (2003-2007)

Source: UNCTAD, 2008

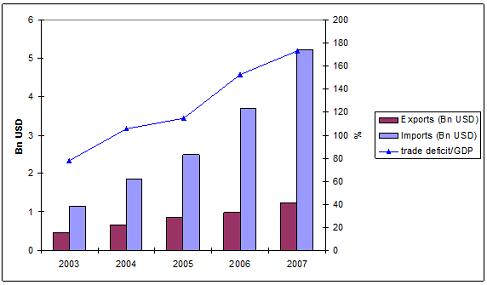

Some causes for concern emerged well before the global financial breakdown. Since 2004, Georgia began to experience a peculiar version of the so-called Dutch disease. According to this theory, when exchange rates are not fixed, raw materials-exporting countries may experience a crisis of competitiveness of other exports due to fast appreciation of the local currency, stemming from the export of natural resources. Georgia is not a raw materials exporter, but it experienced such an appreciation as a result of massive foreign capital inflows. The trend of appreciation of the Lari began due to investments related to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline.[30] During the last five years, FDI dramatically grew, along with increasing international aid, sometimes coming from private donors linked to the new political elite and emigrants’ remittances, which reached 403.1 million USD in 2005 (accounting for 60% of total inflows). At the same time, the Lari nominal exchange rate strengthened by 2.3% in 2003 and 11.9% in 2004, with the rate of appreciation slowing down in 2005, showing a steady growth over the following years.[31] The effects of this appreciation on trade have been huge. Figure 2 shows the impressive degree to which the trade deficit, encouraged by the aforementioned exchange rate dynamics, grew over the last five years, exceeding the GDP in 2004 and reaching the record level of 173% of GDP in 2007.

Fig. 2: Trade deficit in Georgia (2003-2007)

Source: Department for Statistics of the Ministry of Economic Development of Georgia, 2008.

Even if one-fourth of Georgian exports have not been severely hindered by the Georgian version of Dutch disease, since it focuses on internationally traded commodities such as scrap metal and non-ferrous metal, the remaining three-fourths consisting of wheat, flour, sugar, medicine, and motor cars have been seriously damaged, while the balance between tradable and non-tradable sectors has been disturbed. In normal conditions, any macroeconomic imbalance stemming from FDI and international aid is supposed to be temporary, but in these times conditions are all but normal. Due to the financial turmoil, FDI inflows – again, the component of growth accounting for almost 90% of GDP – dropped to 300-400 million USD in the second half of 2008 as opposed to the huge level of 1.5 billion USD in the first half[32] so that they are unlikely to continue to finance the Georgian commercial deficit. Despite the optimism shown by former Prime Minister Lado Gurgenidze in repeating that the downturn will only have an impact on the Georgian economy indirectly,[33] the World Bank estimates that 3.2 billion USD of international aid is needed over the next three years, allowing Georgia to land softly from the FDI shock stemming from the combined effects of the August war and the global financial crisis. Furthermore, the argument of the weak trade and financial links with the US is a poor one. Most of Georgia’s regional trade partners – namely Turkey,[34] Russia, and Ukraine – have been hit hard, and Georgian authorities would be advised not to rely on them, taking into account that given the poor industrial basis it is hardly credible that foreign trade will rescue the country. In any case, if the Lari is going to devaluate, there is room for some improvement as far as competitiveness is concerned. Unfortunately, in the aftermath of the war the Central Bank opted for a strategy of “imperceptible devaluation” instead of consistently allowing devaluation. Given the emergence of panic, which turned into a massive withdrawal of deposits and conversion to dollars, the effort required 300 million USD to be drained from the foreign reserves. The strategy was successful to the extent that the Lari lost only 2.5% against the dollar. What is questionable is the whole strategy of defending an overvalued currency that, on the one hand, does not allow for the reduction of the trade deficit yet, on the other hand, is not reducing the inflationary pressures stemming from the choice to avoid a banking crisis by renewing the commercial banks refinancing and cutting interest rates.[35]

Energy-related Investments as a Case Study: Toward the Marginalization of the Caucasus?

Much of the FDI in Georgia during the last five years is related to the transport infrastructures for hydrocarbons. The previous section already underlined the impact of the BTC-related capital inflows in triggering the Lari’s over-appreciation path. Until now, Georgia benefited from its geographical position, making the country the only outlet for Caspian resources to reach the Western market, bypassing politically detrimental alternatives such as Russia and Iran. This position provides a geopolitical rent, defined as the ability to obtain political and economic gains from major international actors thanks to a strategic geographical position.[36] These actors provide an amount of a resource to the rentier state, reducing many constraints limiting the government’s room for maneuvering, both internally (ability to reduce the tax burden and building a consensus damaging for democracy) and externally (perception of political credit, providing incentives for a more assertive foreign policy).[37] This kind of rent, like other rents such as the oil one, is rather unstable and dramatically dependent on the strategic priorities of these major actors that provide resources to the rentier. Moreover, the rent enjoyed as a strategic energy-transit country strongly depends on the profitability of investments, the strategic perception of the energy resources necessary for transit through the rentier territory, and the evolution of the international position of the alternative transit countries. Due to this position, Georgia has been able to procure political and economic gains thanks to strained US-Iran and US-Russia relations, and because of the high price of hydrocarbons, which make the development of the Caspian resources profitable. This section will describe how these gains are at risk of disappearing in the coming years because of the systemic impact of the financial crisis and the August war on the decisions concerning energy-related investments in the Caspian basin.

As regards the politics of energy, it is useful to consider a historical perspective to decipher the strategic relevance of Georgia for the Western interests. Since the early 1990s, the US Administration laid down dual role regarding Caspian basin hydrocarbons: at a global level, reducing the global energy dependence on the Gulf to increase US foreign policy options in that area; and at a regional level, encouraging the FSU countries to find alternative export routes in order to emancipate their transition path from the influence of Russia.[38] This approach was arguably inconsistent with the “Russia first” policy of the first Clinton Administration, but some consistency can be found with Brzezinski’s assumption, which implies that this strategy was necessary to help Russia shed the burden of a self-damaging imperial legacy.[39] The EU followed suit by providing several institutional frameworks to its infrastructural strategy, such as the INOGATE program (operational since 1999) and the Baku Initiative of 2004.[40] In the early 1990s, viewing the Caspian as the “oil Eldorado” strongly influenced the Western approach during the following decade. The Western pressure on regional regimes and international oil companies (IOCs) to invest in multi-pipeline strategies, despite the IOCs rising skepticism about the region’s potential, led many commentators to talk about a new Great Game,[41] with politics always trumping economic considerations. In the end, the Caspian basin turned out to be anything but an Eldorado. The amount of hydrocarbons in the region is far from impressive and will never be able to replace Gulf oil. Moreover, given the climatic and morphological complexity of the region, the cost of extraction is substantially higher than other oil provinces.[42] The main achievement of the Western strategy has been the BTC, finally profitable thanks to the rising oil prices of the last years as well as – in a very long-term perspective – the possibility to channel oil from North Caspian Kashagan field through the pipeline.[43] Into the framework of this petro-political game, Georgia benefited from the possibility of attracting Western attention by relying – among other factors – upon its geopolitical rent, because its status of a sole transit country allowed Caspian basin resources to bypass Russia (helping the EU to curb its energy dependency) and Iran (complying with the US interests, since an EU dependent on Iranian gas would be a geopolitical nightmare). The Western attention towards Georgia peaked with the 2003 Rose Revolution, strongly supported by the Republican administration, which, even more than the previous one, invested US prestige and money in Georgia by marking a significant upgrading of the US policy in the area.[44] Over the last few years, the energy side of the strategy, aimed at channeling Caspian hydrocarbons through Georgia, lied in the active promotion of the Nabucco pipeline and the revival of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) project, aimed at filling Nabucco with the Turkmen gas. Both projects – standing or falling together[45] – meet the opposition of Russia, which undertook several responses: first, striking a deal with Turkmenistan to ensure that future exports will fill the Prikaspiyskiy branch of the Central Asia-Centre (CAC) system by promising to buy the Turkmen gas at the European netback price.[46] Second, inconsistently trying to prevent Azerbaijan from filling Nabucco by promising to buy all Azerbaijani gas coming from Shah Deniz[47] and threatening, in the past, to cut off the Russian gas supply to Azerbaijan to push the country to use the Shah Deniz gas to meet the rising domestic demand, instead of exporting it westwards.[48] The latter approach is no longer effective since Azerbaijan has finally stopped Russian gas imports, but the first one has achieved a considerable result with the agreement between Russia and Azerbaijan signed in July 2009 on the purchase of 500 mcm of Azeri gas per year by Gazprom as of 2010. These developments clearly show the Russian determination to maintain a grip over the Caspian gas grid.[49]

The question is now if the systemic change stemming from the financial crisis is likely to occur according to the previous sections’ perspective, the political support for controversial energy projects might weaken considerably. As the new US Administration is expected to have a strengthened dialogue with Russia, aimed at keeping the Russians in the multilateral solutions of more relevant issues, pressures for projects able to weaken Russia and to exacerbate its feeling of encirclement might decrease. However, so far, this does not seem the case in the light of the aforementioned intergovernmental agreement of the 13 July 2009 between the Nabucco transit countries to give a legal basis to the pipeline, but it has to be noticed that the US Special Envoy for Eurasian Energy Richard Morningstar stressed that Russia is free to supply gas to the pipeline reiterating the American opposition to any eventual Iranian participation.[50]

If the combined effect of the financial crisis and the August war is likely to weaken the political support for investments in South Caucasus aimed at freeing the Caspian resources from the Russian control, it is even more likely to undermine the economic viability of these investments that has already been questioned because of the insecurity of the supply of gas. With the emergence of the financial crisis, international hydrocarbons prices dropped significantly from 142 USD/bbl to 48 USD/bbl within less than four months. OPEC gave an early warning by assessing to which degree the collapsing world prices are threatening the investments, and it assumed that a price between 70 and 80 USD/bbl would make them profitable.[51] Remarkably, more than 10 strategic projects worldwide, although not clearly identified, are expected to be hindered by any price lower than 60 USD/bbl.[52] Despite the abovementioned agreement of the 13 July, the Nabucco pipeline still faces some perplexity due not only to the security of supply, but even to impact of the crisis on private investors.[53] The European Investment Bank reiterated its willingness to ease credit, but the partial coverage is still subordinated to persisting doubts about technical and economical soundness and the security of the private participation is part of it.[54]

Although oil prices are growing, it could be useful to provide some calculation considering a price between 55 and 60 USD/bbl. Assume that gas prices drop to 0.165 USD/cm, a price which is consistent with the aforementioned long-term level of oil prices (though they could rise again). According to a positive scenario, with Nabucco shipping 8 bcm/y between 2013 and 2015 and 31 bcm/y as of 2016, four and a quarter years would be needed to cover the 10.3 billion USD investment cost. According to a pessimistic scenario, between 3 and 5 bcm/y could be carried from 2013 to 2015, and 20 bcm/y as of 2016. In this case, the investment coverage would require between five and a half and 6 years. With the high prices on the energy markets before the financial turmoil, three years would be needed to make the investment profitable. Obviously, this simple calculation has no scientific value and does not take into account several crucial additional variables, but it is sufficient as far as the sensitivity of investments in the Caspian basin to the hydrocarbons’ international prices is concerned. In this respect, even a non-exporting country relying only on a transit rent like Georgia would be dependent on high hydrocarbons prices to attract investments and benefit from a “geopolitical rent”.

Added to these concerns is the growing risk associated to infrastructural investments in Southern Caucasus in the aftermath of the war. Although Russian bombers did not target any energy facilities, the coincidence of an explosion in the Turkish section of the BTC close to the Georgian border a few days prior to the military operations raised some concern about the possible targeting of the pipelines.[55] This is strongly connected to the systemic implications explored above, as the war demonstrated that the Western guarantees for Georgia lacked substance, and the integrity of the oil and gas corridor depended simply on Russian good will.[56] A clear sign of this came from the BP decision to temporarily stop the oil flows through Georgia to divert part of them through the Russian facilities, while Kazakh Prime Minister Karim Masimov ordered KazMunajGaz to study whether the domestic market could absorb the exports envisaged for transit via Georgia. Even the Azerbaijani company SOCAR re-directed a portion of its exports, normally sent through the Georgian terminal of Kulevi, towards the Iranian port of Neka during August and September 2008.[57] As a result, many commentators argue that the weakness of the Western deterrence will raise serious doubts among lenders and investors facing higher insurance costs by reducing the viability of both Nabucco and TCP,S and the strategic relevance of Georgia within Western agendas.

Conclusion

According to a hegemonic stability perspective, both the global financial crisis and the August war in the Caucasus can be interpreted as signs of the decay of the unipolar order emerging from the collapse of the USSR. The Georgian attempt to reassert control over South Ossetia by force and the consequent Russian invasion demonstrated the inability of the hegemon to deter a great power from using force beyond its borders and its unwillingness – or inability – to exert retaliation. According to the theoretical framework, this event is connected to the acceleration of the global financial crisis to the extent that the hegemon’s military might, which is a crucial tool to ensure international security as a public good, allowing international markets to work properly, turned out to be insufficient to prevent the Russian invasion by casting a huge shadow over the confidence in the systemic equilibrium and the legitimacy of a trade and financial system articulated in order to ensure the hegemonic interest of an actor of the system. This does not mean that the Caucasus war triggered the global financial crisis. It only contributed – among other factors – to reveal structural weaknesses affecting the hegemonic international position of the US, no longer able to provide credible deterrence as a pivotal international public good. If these events are likely to accelerate a shift toward a multipolar order, the consequences for Georgia could be detrimental. The new US administration is showing the willingness to address some relevant issues on a multilateral basis. The US needs Russian cooperation to cope with the Iranian nuclear program and the Afghan crisis; thus the US could be forced to reduce their engagement in Georgia and the FSU. Both NATO delaying the MAP for Georgia and Ukraine and the EU’s post-war strategy can hardly please the Georgian government.

[1] Such an attitude reflects the relatively low level of integration of Russia within the main schemes of economic interdependency, and the mistrust of the Moscow’s political and military elite against a globalization perceived as a tool for US dominance over the world. President Medvedev declared during his State of Nation Address that the South Ossetian conflict and the financial crisis have the same origins, and both have the effect of destabilizing the basics of the world order (see Dmitriy Medvedev, “Poslanie Federal’nomu Sobraniyu Rossiyskoy Federacii,” [Speech to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation] November 5, 2008, available at http://www.kremlin.ru/appears/2008/11/05/1349 _type63372type63374type63381type82634_ 208749.shtml). Karaganov underlined these points, according to the concept of the US “imperial overstretch” (Sergey Karaganov, “Mirovoy Krizis: Vremya Sozdat’,” [The World Crisis: a Time for Creation], Rossiya v Global’noy Politike, vol. 6:4, (2008): 8-16).

[2] Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression – 1929-1939, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986), 291-308.

[3] John Conybeare, “Public Goods, Prisoners’ Dilemmas, and International Political Economy,” International Studies Quarterly, vol. 28:2 (1984): 5-22; Joanne Gowa, “Rational Hegemons, Excludable Goods and Small Groups,” World Politics, vol. 41:2 (1989): 307-24.

[4] Robert O. Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 31-35.

[5] Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: the Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), 33-73.

[6] Robert Cox, “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 10:2 (1981): 126-55.

[7] Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 12-13.

[8] This concept has been suggested for the first time by conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer to describe the emerging unipolar order as a stable and long-lasting one according to the fundamentals of the hegemonic stability theory (See Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 70:1 (1990-91); also available at: http://www.foreignaffairs.org/19910201faessay6067/charles-krauthammer/the-unipolar-moment.html).

[9] Barry Buzan, The United States and the Great Powers: World Politics in the Twenty-First Century, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 53-56.

[10] Joseph S. Nye, “The Limits of American Power,” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 117:4 (2002-03), 545-59.

[11] Robert Gilpin, “The Theory of Hegemonic War,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 18:4 (1988): 591-613.

[12] Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of Great Powers (New York: Random House, 1987), 665-90.

[13] Barry Buzan, The United States and the Great Powers: World Politics in the Twenty-First Century, 151-57.

[14] The trade and fiscal position of the US worsened dramatically during the last few years due to the strain of two wars, as well as tax cuts.

[15] This is a problematic point, as with reference to the South Ossetian issue, Russia was a status quo actor, of course. By taking the systemic level into account, Russia is one of the more revisionist powers of the system given its relatively limited interaction with it (e.g. compared to the level of China’s interdependence with the hegemon) and its widely recognized push for multipolarism.

[16] In dramatic fashion, the acceleration of the downturn took place in the month of September with the fall of Lehman Brothers and after a steady and low pace of decline dating back to the 2007 subprime crisis. Russian RTS index started to fall dramatically in May 2008 – several months before the war – and continued its path of decay during the following months. In the aftermath of the war, Russia suffered from capital outflows much more than the stock market decline. For stock market data, see www.rts.ru and www.djindexes.com.

[17] William Gross from Pacific Investment Management Company blatantly said, “Take away our military might, and a lower rating would be a near-unanimous opinion” (quoted in Aaron Lucchetti, “Some Questions on US Debt Rating,” The Wall Street Journal, December 7, 2004).

[18] Deputy Foreign Minister Giga Bokheria emphasized that “President Obama […] expressed very explicit and crucial support and I’m sure this friendship, which is based on strategic interests, is going to continue.” Even the Tbilisi State University Rector Giorgi Khubua noticed that Senator Biden was among the early proponents of a billion-dollar post-war aid package for Georgia. (Both quoted in Giorgi Lomsadze, “Georgia: Tbilisi Contemplates How the Obama Administration Will Approach Caspian Basin,” Eurasia Insight, November 6, 2008, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insightb/articles/ eav110608a.shtml.)

[19] European Commission, “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council – Eastern Partnership,” COM(2008) 823/4.

[20] NATO press release, “Allies Discuss Relations with Ukraine and Georgia and Send a Signal to Russia,” December 3, 2008, http://www.nato.int/docu/update/2008/12-december/e1203b.html.

[21] Ariel Cohen, “Yankees in the Heartland: US Policy in Central Asia after 9/11,” in Eurasia in Balance: the US and the Regional Power Shift, ed. Ariel Cohen (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), 69-100.

[22] Philip P. Pan, “Biden Offer Georgia Solidarity,” The Washington Post, July 24, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/23/AR2009072301541.html

[23] Marlène Laruelle, “Kazakhstan Challenged by the World Financial Crisis,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst, November 12, 2005, http://www.cacianalyst.org/?q=node/4979.

[24] IMF, “IMF Set to Lend Ukraine $16.5 Billion, In Talks with Hungary,” IMF Survey online, October 26, 2008, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2008/car102608b.htm.

[25] The loan accounts for almost eight times the size of the Ukrainian contribution to the IMF. See Roman Olearchyk & Alan Beattie, “IMF Outlines $16.5bn Ukraine loan,” Financial Times, October 27, 2008.

[26] Although, in theory, Russia is supposedly financially well placed thanks to the lonely and unpopular crusade of Aleksey Kudrin (Russian Minister of Finance), albeit with the same problems of banks’ undercapitalization and reliance on collapsing raw material prices.

[27] Michael Stott, “Russia Acknowledges Financial Crisis Has hit Hard,” Reuters, November 21, 2008, http://www.reuters.com/article/reutersEdge/idUSTRE4AK4L620081121.

[28] Nina Akhmeteli, “Will the American Economic Crisis Hit Georgia?” Investor.ge, April 2008, http://www.investor.ge/issues/2008_2/01.htm.

[29] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2008”, UNCTAD, http://www.unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs/ wir08_fs_ge _en.pdf.

[30] Vladimer Papava, “The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline: Implications for Georgia”, in The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan: Oil Window to the West, eds. Frederick Starr and Svante E. Cornell, (Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2005), 123-139.

[31] National Bank of Georgia “Annual Report 2007,” National Bank of Georgia, http://www.nbg.gov.ge/uploads/publications/annualreport/tsliuri_angarishi2007eng_bolointernetistvis.pdf.

[32] Isabel Gorst, “Georgia Seeks Aid Pledges to Plug Foreign Investment Gap,” Financial Times, October 4, 2008.

[33] According to Gurgenidze, the foreign aid is needed mainly to recover from the infrastructural damages of the war, as the global financial meltdown is supposed to have turned the corner and the reduction of the FDI is going to affect the entire world and not only Georgia. Further, Georgia is not planning interventions in the real sector and is instead getting stand-by facilities to increase the central bank’s reserves in times of financial uncertainty (Lado Gurgenidze, “Putting Georgia on a Path of Recovery,” IMF Survey Online, October 21, 2008, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2008/INT102108A.htm).

[34] Ian O. Lesser, “Turkey and the Global Economic Crisis,” (working paper, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, November 2008, http://www.gmfus.org//doc/Lesser_Turkey _Analysis_EconomicCrisis _Final1.pdf).

[35] The basic interest rate has been reduced by 2 points (from 12% to 10%) in order to reduce the incentives to buy Central Bank securities (Vladimer Papava, “Post-war Georgia’s Economic Challenges,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst, November 26, 2008, http://www.cacianalyst.org/?q=node/4991).

[36] Philippe Le Billon, “The Geopolitical Economy of Resources Wars,” in The Geopolitics of Resources Wars: Resources, Dependence, Governance and Violence, ed. Philippe Le Billon (London: Frank Cass, 2005), 1-28.

[37] Øystein Noreng, Crude Power: Politics and the Oil Market (London: I. B. Tauris, 2005), 52-102.

[38] Anoushiravan Etheshami, “Geopolitics of Hydrocarbons in Central and Western Asia,” in The Caspian: Politics, Energy and Security, ed. Shirin Akiner (London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), 63-89.

[39] Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives, (New York: Basic Books, 1997), 48-56.

[40] The Baku Initiative involves the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Transport and Energy and Directorate-General for External Relations along with 14 third countries, including Russia as an observer. It is aiming at the progressive integration of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea region energy markets with the EU markets. Such a process implies progressively converging energy policies on issues of trade, transit and environmental rules as well as standards (See http://www.inogate.org/inogate/en/baku-initiative).

[41] Matthew Edwards, “The New Great Game and the New Great Gamers: Disciples of Kipling and MacKinder,” Central Asian Survey, vol. 22:1 (2003): 83-102.

[42] Andrey V. Belopolsky and Manik Talwani, “Geological Basins and oil and Gas Reserves of the Greater Caspian Region,” in Energy in the Caspian Region, ed. Yelena Kalyuzhnova (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002), pp.13-33.

[43] The main option is to increase trans-Caspian shipments through the Kazakh Caspian Transportation System to Baku. The system was envisaged to bring an additional 500,000 bbl/d, to be raised up to 1 million bbl/d as of 2011 in case of a considerable expansion of the BTC capacity ( IEA, “Perspectives on Caspian Oil and Gas Development,” working paper, IEA, December 2008).

[44] By carrying 1 billion barrels of crude oil per day, the BTC is not making a serious dent in the world’s thirst for Gulf oil (Nicolai N. Petro, “Prisoners of the Caucasus Unite,” Herald Tribune, August 20, 2008). Moreover, its ability to help the Caspian FSU countries to reduce their dependence on the centralized Soviet infrastructural panorama did not result in a clear political emancipation of these countries, as multi-vectorial and balanced foreign policy is still going on in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

[45] Niklas Norling, “The Nabucco Pipeline: Reemerging Momentum in Europe Front Yards”, in Europe Energy Security: Gazprom Dominance and Caspian Supply Alternatives, eds. Svante E. Cornell and Niklas Nilsson (Stockholm and Washington: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute – Silk Road Studies Program, 2007), 127-140.

[46] The agreement was reached at presidential level on May 12, 2007. It is part of a broad package, including a 25-year gas purchasing contract (Vladimir Socor, “Russia Surging Farther Ahead in Race for Central Asian Gas,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, May 16, 2007, http://www.jamestown.org/ edm/article.php?article_id=2372168).

[47] RIA Novosti, “Gazprom Ready to Buy Azerbaijani Gas at Market Prices,” June 4, 2008, http://en.rian.ru/ russia/20080604/109215278.html.

[48] Johnatan Stern, “The Cut-Throat Energy Politics of Russia and Turkey,”Europe’s World, vol. 5:2 (2007), 125-29.

[49] For a broad description of the Russian interests at stake in the Caspian region’s infrastructural policies, see Stephen Blank, “Infrastructural Policy and National Strategies in Central Asia: the Russian Example,” Central Asian Survey, vol. 22:3-4 (2004): 225-48; and Johnatan Stern, The Future of Russian Gas and Gazprom, (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 72-79.

[50] EurActiv, “EU Countries Sign Geopolitical Nabucco Agreement,” July 14, 2009, http://www.euractiv.com/en/energy/eu-countries-sign-geopolitical-nabucco-agreement/article-184062

[51] The Associated Press, “OPEC Members Say Low Oil Prices Risk Investment,” October 28, 2008, http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/10/28/business/EU-Britain-Oil.php.

[52] Chua Baizen, “Aramco: Low Oil Prices Threatening Investments,” Arabian Business, November 8, 2008, http://www.arabianbusiness.com/537457-aramco-low-oil-prices-threatening-investment.

[53] New Europe, “Credit Crunch May Delay Nabucco,” September 29, 2008, http://www.neurope.eu/ articles/89958.php.

[54] EurActiv, “EIB Ready to Help Finance Nabucco Pipeline,” July 24, 2009, http://www.euractiv.com/en/energy/eib-ready-help-finance-nabucco-pipeline/article-184362?Ref=RSS.

[55] Orhan Coskun and Lada Yevgrashina, “Blast Halts Azeri Oil Pipeline through Turkey,” Reuters, August 6, 2008, http://www.reuters.com/article/GCA-Oil/idUSSP31722720080806.

[56] Sergey Blagov, “Georgia: Pipeline Routes on a Pwder Keg,” ISN Security Watch, August 20, 2008, http://www.isn.ethz.ch/isn/Current-Affairs/Security-Watch/Detail/?ots591=4888CAA0-B3DB-1461-98B9-E20E7B9C13D4&lng=en&id=90265.

[57] IEA, ““Perspectives on Caspian Oil and Gas Development,” (working paper, IEA, December 2008).

[58] Anatoliy Medetskiy, “War Casts Cloud Over Pipeline Route through Georgia,” The Moscow Times, August 14, 2008.